Why do I love festivals so much? One reason might be that I find myself being surprised anew every time. Only on festivals do you find gems you would have otherwise never encountered. This holds true for classic films; doubly so for virtual reality experiences. The VR animated film Lucid turned out to be just that kind of discovery at Venice VR, where it celebrated its premiere. The captivating adventure revolving around a mother-daughter duo asks the big questions of life – and demonstrates, almost in passing, the definition of virtuous storytelling in VR.

Lucid is a rollercoaster through love and life

The film begins on a peculiar scene: Astra, a young woman, finds herself stood within a dark underwater world, talking to an invisible person. It quickly becomes apparent that Astra is not inside reality, but rather an intruder in a foreign consciousness – her mother’s, Eleanor, a famous author of children’s books, who is lying in a coma following a serious accident. Astra has entered her mother’s mind with the help of a new technology and a helmet sprouting a mess of cables. She wants to say farewell to her mother. In the real world, an attentive scientist with whom she communicates via radio watches over Astra sitting at the bedside of her terminally ill mother.

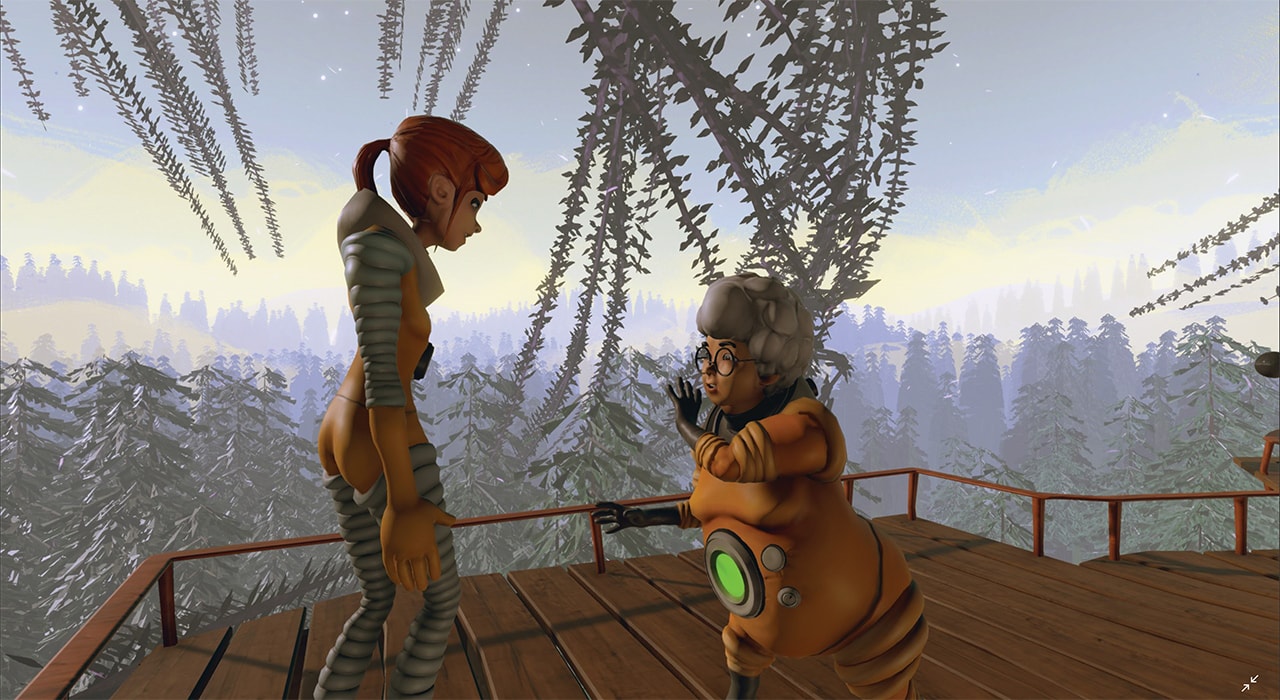

Astra’s presence in Eleanor’s consciousness triggers something unexpected: Eleanor’s mind gradually comes to life. In her comatose dream, she has slipped into the guise of her favorite character from one of her own books. When Astra first finds her, she is jumping cheerily about in her treehouse high above the canopy. Eleanor is unaware of her body lying in hospital, and she doesn’t recognize her own daughter either. Astra doesn’t let this hold her back. In order to fully reconstruct Eleanor’s memories and bring her back from her coma, Astra bravely decides to accompany her mother through her childhood fantasy world.

What follows is a breathless ride through fragmented scenes of Eleanor’s life and books. While doing so, the London-based production company Breaking Fourth demonstrates its mastery of filmic storytelling in immersive worlds. The treehouse, the gloomy forest, the ice desert, the rambling flight capsule – I experienced all of this up close in VR. The colorful world in Eleanor’s head is rich in variety and imaginative details, and perfectly tuned for VR’s visual experience. Here, Lucid combines the best from VR and film.

Filmic dramaturgy meets VR

While VR might make things prettier and profoundly more immersive – the story would have also been exceptional as a classic short film in 2D. Despite its brief runtime of just 16 minutes, the VR film struck me like a full-length feature film. This is due mostly to the artfully crafted script – one that ran through seven iterations until its completion. It was written by the author Islay Bell-Webb in close cooperation with the producers. The direction was handled by Pete Short from Australia.

“Lucid is a story of love, adventure and letting go.“ Pete Short harmoniously states in the press material. “I have been waiting a long time to tell this story. VR finally allows me to tell it in a way that does it justice. The audience is granted access to Eleanor’s mind to share the final, intimate moments between a mother and a daughter.”

The result is a declaration of love for the deep bond the two women share. At the same time, the film ponders questions about life and death any human being will have to face eventually.

Though I hate to admit it (everyone likes to act tough…) – there were precisely two VR experiences in Venice that made me cry, Lucid being one of them. As I took off the tear-dampened goggles, I was all the more bewildered to find myself directly facing the smiling faces of David Kaskel and Ken Henderson, the two producers and founders of Breaking Fourth. Having composed myself again, we managed to have a little chat before I had to hurry off to the next VR demonstration.

The composition: how does one tell a VR short story?

On the next day, Breaking Fourth CEO David Kaskel, the film’s ideator, granted me an extensive interview. I wanted to know what, to him, makes a good story in VR; and why, of all things, he chose this subject for Lucid. It is very important for short forms such as VR to quickly elucidate the main emotional themes to the viewer, he says.

“Why did I choose these things? There is already a lot of awareness of what happens towards the end of life and dementia and a lot of awareness of a mother-daughter relationship. I think we look for – if it is under 20 minutes – what we are going to be able to tap into quickly. Because of the complexity of VR, we also know that people can’t pay as much attention to everything that’s going on. People often want to explore an area visually, and they let their minds wander a little bit more.

For us, it is important in VR to hit an emotional chord. I think in order to have a broader market we are looking for kind of bigger themes, whether it’s loss or, in some cases, violence or intense love or longing. We are trying to think up front: How do we have a sweeping arc that will deal with this, that will take someone through that story?”

I was particularly impressed with the story’s narrative that progresses decidedly unchronologically – instead beginning in the middle of the action of the first scene. The backstory only gradually comes to light; quite common for classic film – still a rarity within VR in my opinion. David revealed to me why the filmic beginning worked so well for Lucid:

“Again, we wanted to get people involved very quickly. So we put them right there, right at this moment. I also think that mystery hooks people in. So, you give them enough clarity to understand one thing – but also a bit of a mystery, so that they want to push forward. We thought starting right there and then, filling in the backstory, is what keeps a narrative interesting in what’s going on. Why is she saying those things? What has just happened? Why did she go in in the first place? I think for that you need to kind of go back and forth a bit.”

At the same time, they want to entertain the viewers – something they’ve achieved brilliantly.

The protagonists: Astra’s and Eleanor’s journey

Eleanor plays a big role in that, with her bubbly and humorous character and unrelenting stubbornness. I took a liking to her after only a couple of minutes. In order to represent the breakneck journey through her memories as accurately as possible, the team sought the help of two neuroscientists specialized in – this much I may surely say – dementia. They assessed how realistic some of the situations were; whether specific memories could follow certain other ones. Moments of clarity alternate with gaps in memory; recognition with forgetting. The film regularly jumps between Eleanor’s past and her fantasy world. Any ideas ruled as implausible by the experts were canned, says David.

As vivid and captivating Eleanor and her memories may be: Astra remains the main character of the story. It is her who undergoes profound developments throughout the film. For David, the relationship between child and parent was especially important, taking the longest amount of time to get right:

“We had people of different ages. I’m the oldest of the group, I’m in my 50s. We have people in their 20s, and everyone had a very different sense of what a parent’s responsibility is to a child and what a child’s responsibility can be to a parent. That was something I wanted to explore; having older parents now. What I really wanted to get – and what I worked on with the author – is an acceptance from Astra. I thought it was her journey. She had lot of anger in her and I wanted her to be able to kind of come to terms; understand what it was like for her mother.”

The film is narrated entirely in third person perspective. The viewers do not assume any role; they participate as silent spectators. The Breaking Fourth team consciously decided against a first-person perspective, or even interactive scenes, wanting to show the plot and the protagonists’ development as intimately as possible and without interruptions.

UPDATE February 2019: Lucid is now available on Viveport

I got to see the film as a Roomscale experience on an Oculus Rift. In effect, though, most scenes are designed for a 180-degree field of vision. This allowed me to explore the world around me, while also being able to comfortably follow the action from a seated position.

The reason for this might be that Lucid is also poised to appear as a 360-degree film, sometime maybe…

But – and now jump up from your seat and do a little dance – Lucid is now available for HTC Vive or Oculus Rift headsets, exclusively on Viveport and in gorgeous room-scale VR. Don’t miss it!

There is also a very nice interview on the official Vive blog.

UPDATE April 2019: A second version in 360 degrees has just been released on the platform Veer.tv for Oculus Go and Oculus Rift. That are great news especially for the Go-users among you (if you have a Rift at home, I still recommend the full version in room-scale VR). First, you need to download the app, then you can buy the film for 1,99 $.

This article first appeared in a shortened, German version on VRODO.de.

Translated by Jan Mc Greal

2 comments on “Lucid, My Favorite VR Film at Venice VR”