Some time ago, I reported on the big attractions of 2018’s Tribeca Film Festival and wrote about my favorite films. However, there was much more to see! I found myself in Syria, I interrogated travelers as a US customs official, I saw Africa and stood in Japan. I experienced what it feels like to be discriminated against and revealed very personal things about me. To round things off, I made music as a fat little bunny. Part 2 of my Tribeca highlights of VR.

To be clear: not all of the experiences of the Tribeca Virtual Arcade were pleasant experiences. Some were thought-provoking, others quite disconcerting. As happens in any medium, artists also push the boundaries of VR and AR.

Crossing Borders

Both of the following projects are true border crossers, as spectators cross borders in both, while the films themselves break boundaries.

The New Yorker production company iNK Stories rightly describes their experience Hero as a “deeply provocative, immersive, multisensory narrative,” a project they have previously shown at the Sundance festival. At Tribeca, Hero was awarded the branch-spanning Storyscapes prize, which honors innovations in storytelling (though only a handful of the experiences found in the Virtual Arcade were nominated anyways).

It all started with the fact that Hero actually was not exhibited in the Virtual Arcade. Instead, a friendly employee led me from the fifth floor down to the first floor. That should have been my first warning. As I passed through the black curtains, I was struck with an immense heat. It was at least 25 degrees centigrade – accompanied by a smell. Not an unpleasant one, more so resembling the feeling of alighting from a plane in a foreign country, taking in the air and all its scents for the first time. I was in Syria now, as the staff member told me with an earnest expression on her face. Just like in Jack, I was provided with a backpack. I had barely entered the VR scene and immediately I could feel my surroundings – a very real wall to my back and a couple of tires lying on the ground, reproduced in my headset. I watched kids playing peacefully and heard the bustle of a little market in the background. Then it began: a bomb! An earthshattering explosion – then I was veiled in screams, dust and thick smoke rendering warped shadows stumbling through the chaos. I was cowering behind a steel barrel when a dog leapt at me from the smoke, to lead me to the innards of a destroyed building. I passed through a burning door, hot from the flames; actually hot. Then I had to fumble my way along a wall across a steep drop. I was scared at first, and my entire body was shaking, but upon hearing a scream come from the far end of the house, I somehow managed to cross the abyss. I found them there. Behind an semi-collapsed wall, a father with his little daughter. She was covered in rubble, with her head on her father’s lap, him shouting for help. I felt powerless. All I could do was hold her hand through a hole in the wall and pull. The futility felt especially shocking when I touched a real, human hand: warm, and reaching out for help. It was the employee’s hand, who had silently accompanied me throughout the entire ordeal.

That is when it all ended. I couldn’t have stomached a second more. Hero makes the horrors of war palpable in a severe way. It aims to shock by any means necessary. The only thing that allowed me to maintain at least a semblance of detachedness – a remoteness I could not have done without – were the computer-generated characters. These, at least, did not appear a hundred percent real.

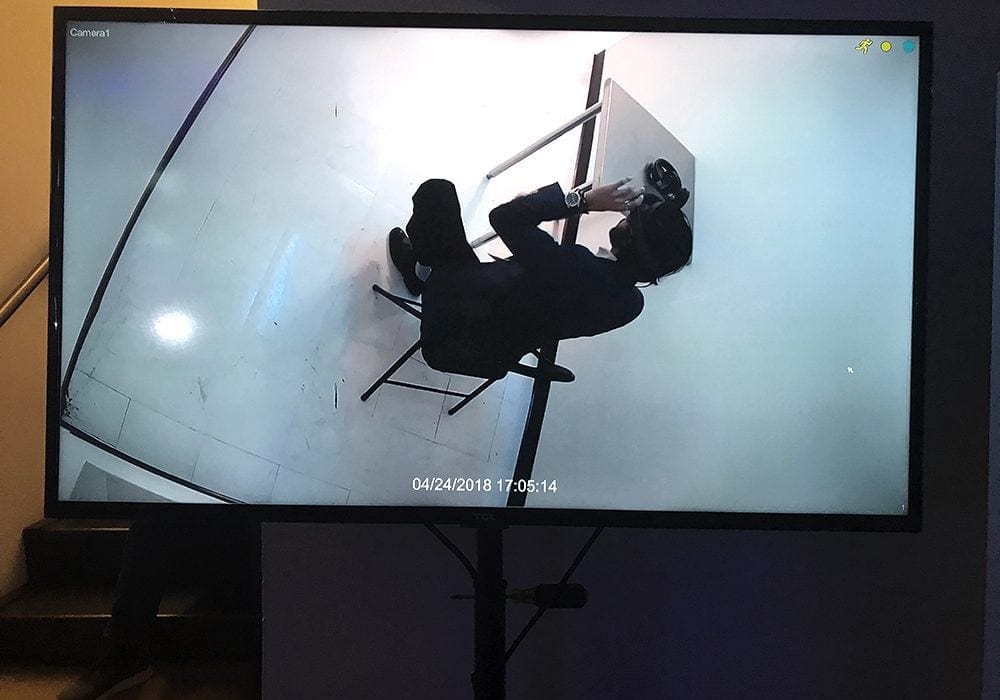

In contrast to this, Terminal 3 incorporates entirely real people. It was one of only two augmented reality experiences of this year’s Tribeca festival. Although it no doubt appears more realistic like this, I do not believe Terminal 3 needed an AR implementation – the experience thrived on its set design, which could have been worked nicely in VR. I was directed into a small room; bare white walls, reminiscent of an airport interrogation chamber. I donned a Microsoft HoloLens, and off we went. I assumed the role of a border official of the United States. The task: interview people and decide whether they may enter the country. Then, a hologram entered the room and sat down across from me. It seemed alien and barely recognizable, but it quickly became apparent that the person facing me was a young woman from Iran, but grown up in the US. She was coming home from a visit to her family.

Questions appeared in my field of vision. To ask them, I had but to utter them aloud. Interestingly enough, I always had multiple options for questioning. My virtual counterpart understood my questions via speech recognition and answered. This way, the story branched out evermore, making every conversation unique. The questions quickly became personal, and making me feel increasingly uncomfortable, so I chose the least intimate question whenever I could. This turned out to be a mistake, as it made me miss a crucial detail: as I learned afterwards, the hologram would appear increasingly lifelike as one got to know them better, or the deeper one pried into their lives. See more on this in the making-of:

Of course, there was another catch. Upon having reached my final conclusion (I let her enter, obviously), I rounded a corner to reach the exit. Around the bend, how startling!, sat the real Helya. She had heard all of my conversation with her digital counterpart. I was happy to meet her – had it not felt like I had already gotten to know her – though likewise, I felt a tinge of embarrassment. I would have rather had a couple of minutes to gather myself and come up with a good question to ask her. Many things could have come to mind, as Terminal 3 is a very current piece on cultural identity – with documentary aspirations. In total, the experience involves the possibility to meet 6 very different people. They all live in the US now, while stemming from Muslim countries originally. Indeed, they belong to a group that has been attracting increasing attention under the US’ current immigration policies. Asad J. Malik, the director himself, comes from Pakistan, and Terminal 3 is based on his personal experiences at US borders. He is one of the six volumetrically captured holograms people can acquaint themselves with in the experience.

Educational

Politics also play an important role in The Day the World Changed, created by well-known Gabo Arora and Saschka Unseld. The experience was one of the few multiplayer interactions at Tribeca 2018. Together with two other festival visitors, we embarked on a journey to Japan. Standing in the ruins of a building that still looks like the direct aftermath of the American nuclear bomb’s deployment during WWII. It was the so-called Atomic Bomb Dome, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. There, we learned a couple of historic facts. Above all though, we saw and heard interviews of eyewitnesses and contemplated pictures of the destruction. The Day the World Changed is a prime example for those wanting to know how best to transfer archive materials such as “flat” pictures and audio recordings to a virtual 3D environment without disrupting the spectators’ feeling of immersion.

Having multiple spectators viewing the VR world is meant to increase emotional ties, as one does not have to traverse the ruins alone and can learn as a group. According to Engadget, the makers plan to develop an expansion for more than three spectators for museums. However, my co-visitors triggered something unexpected in me, as their VR appearances took on the form of dark silhouettes: stooping strangely, transparent, barely visible at times – atomic shadows. This ghost-like effect was certainly intended: when the bomb dropped, many victims only left behind a burnt shadow on the walls. These shadows did not console me, but felt rather menacing. This, however, made me delve deeper into the story. The experience ends on a hopeful note, though: we wiped away a barrage of nuclear missiles pointed at our diminutive Earth with nothing but our hands. A call to action, as The Day the World Changed is chiefly part of the campaign advocating nuclear disarmament.

My Africa showed me yet another facet of documentary-style storytelling in VR, taking place in Kenya and being comprised of two parts. The first part being a quite beautifully shot 360-degree documentary. Young Natlwasha (voiced by Lupita Nyong’o) of the Samburu tribe, leads us through her daily routine. You can already find the experience in the app Within (available right here or in all stores). I had the chance to witness the villagers rescue a baby elephant from a group of poachers. Afterwards, they brought him to the Reteti Elephant Sanctuary, an orphanage for little elephants administered by the community. Following the film, I was once again equipped with a backpack and headset for the active second part, called My Africa: Elephant Keeper. All of a sudden, I was responsible for the care of the rescued elephant. I had to cool him by wetting his ears (with a real sponge), take his blood with a (real) syringe, and could finally feed him with a (real) big feeding bottle. What fun!

Things Get Personal

The project Where Thoughts Go is a self-experiential exercise. I made myself comfortable in a dimly and warmly lit little cave full of pillows and slipped into the headset. In an abstract world, I was confronted with a set of questions. Big questions, such as: when did you fall in love for the first time, and why? If you only had one year left to live, what would you do differently? Little spheres floated all around me. Upon being touched, they opened to reveal beady black eyes staring at me. While we looked at each other, I listened to voice messages left behind by the people who visited the experience before me. I heard their answers to the questions, intimate thoughts on love and death, small and grand stories from their lives. I ran into some voices a few times, which made me feel like I was talking to a good friend.

The press material boasts with the following figure: over 20 percent of testers started to cry in the first prototype. While this may seem drastic, I must say I was touched too. The intimate setting seduces you to become more revealing. I also recorded a number of stories. Who might be listening to them now…?

The team around Lucas Rizzotto aims for nothing less than improving the internet with Where Thoughts Go; himself claiming, in the press material: “Creating a corner in the internet where truthfulness and intimacy between strangers was allowed to flourish – a place where people could acquire perspective in life from the voice of strangers as well as their own – 100% devoid from bias.” He eagerly mixes elements from social media, VR, user created content, gaming, and much more together to this end. The experience at Tribeca was just the prologue. The larger picture envisions the world’s first emotional social network.

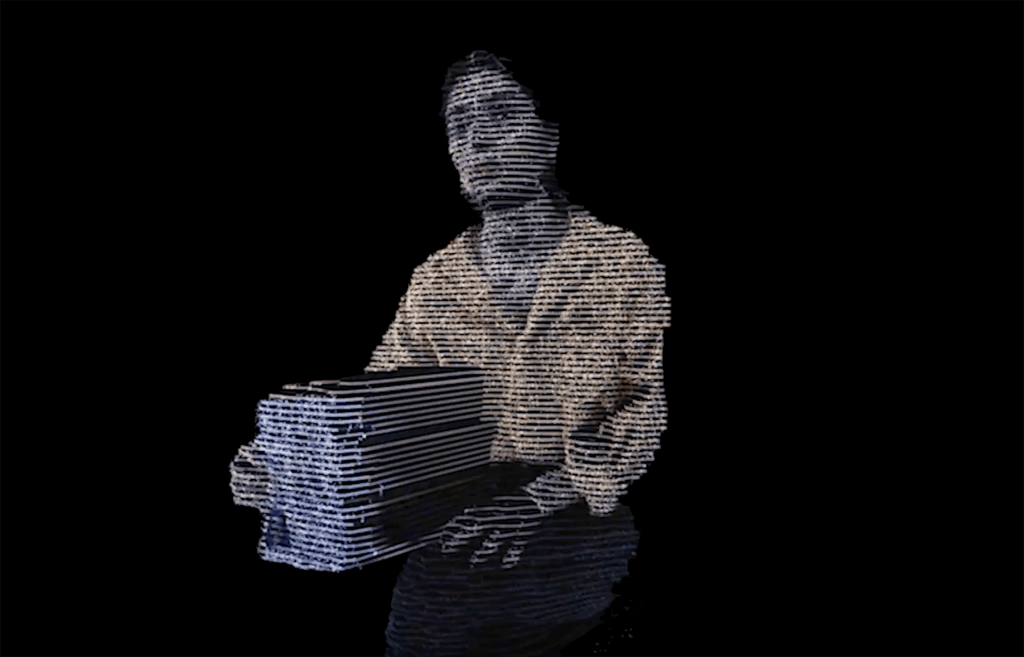

Vestige represents another title that aims to get the tears flowing. Prior to the event, I was very eager to see the film, which is one of the very first volumetrically shot films out there. The film revolves around Lisa, a woman who has lost her true love, Erik. He died at just 40 years old. Speaking over the phone, she recounts her memories of him and the times they spent together. She appears as a visually estranged entity. I found it quite difficult to feel close to her, and I also had trouble with grasping the plot’s thread. The reason for this became apparent later on: specific fragments of Lisa’s memories were played depending on my position in the room and how fast I was moving. Non-linear storytelling – without my even noticing it. Nevertheless, Vestige still stands out thanks to its fascinating fusion of a documentary with a motion picture. While Lisa and Erik are portrayed by actors, the scenes sit on a foundation of long and touching intermittent conversation scenes between the director, Aaron Bradbury, and the real Lisa. After the film, spectators could retreat to a small telephone box before reentering the bustle of the Arcade. There, they could record a voice message if they wanted to, and talk about the people they had lost – much like what happened in Where Thoughts Go. All of these heart-rending stories could be listened to afterwards.

Great Artistry

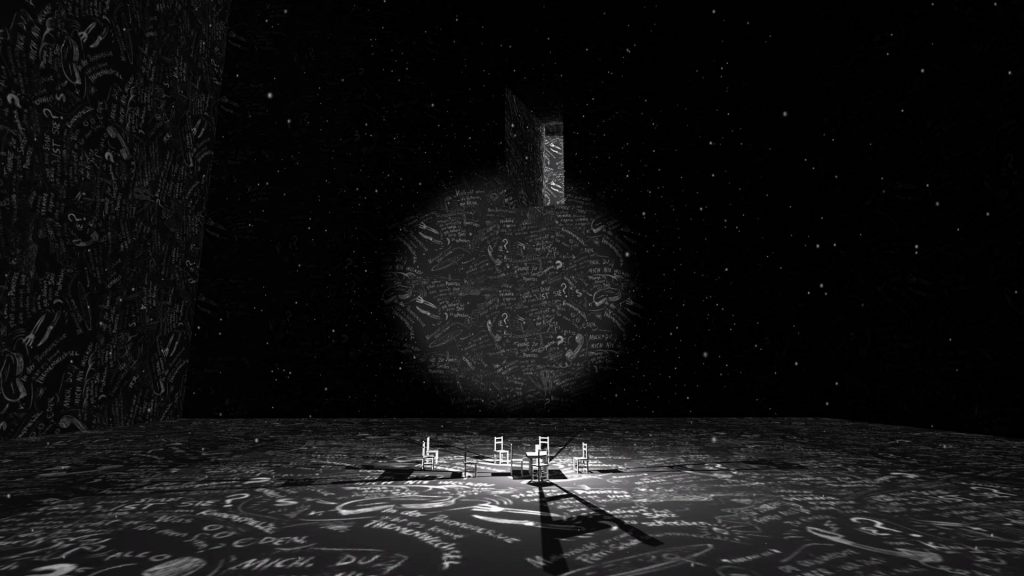

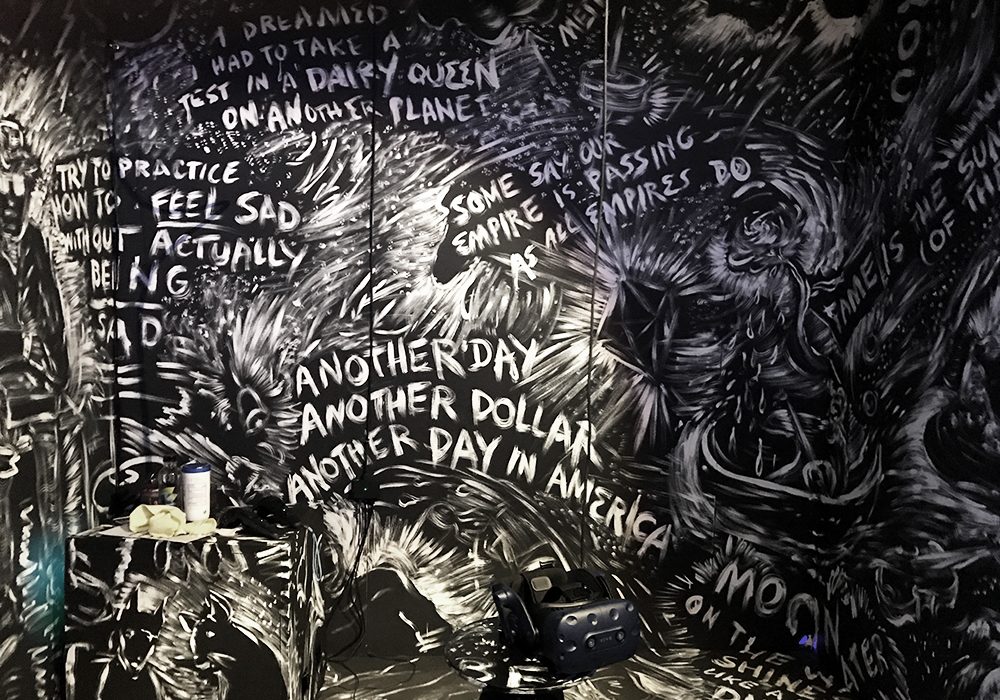

The Virtual Arcade offered a lot of art to be experienced! This doubtlessly included the two large installations Queerskins: A Love Story and Objects in Mirror Are Closer Than They Appear. My favorite, though, must have been the black-and-white world of Chalkroom. This experience also managed to secure a prize at the Venice VR Festival 2017, together with Arden’s Wake. In Chalkroom, the collaborators Laurie Anderson and Hsin-Chien Huang play with words and characters. Users may choose from various chapters and fly, draw, or just listen. Oh, one must have been there to have experienced it – I could have spent hours there. Luckily, Chalkroom can be viewed at the Phi Center in Montréal until mid-August.

The Prettiest Game

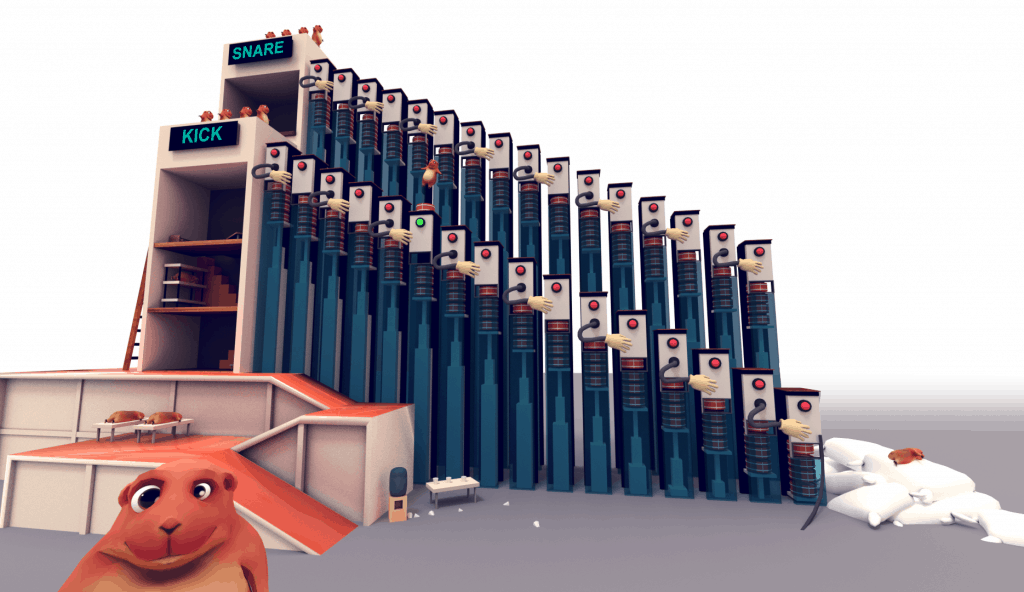

I felt the same way when I visited the probably cutest and most imaginative experience in all of Tribeca 2018. Lambchild Superstar is something I would buy immediately to make music together with all of my friends. That’s what it’s all about: within a multiplayer setting, people can learn the fundamentals of music together – in the most amusing way possible! We wiggled across a playground, from one instruments to the next, as two fat little bunnies. These instruments were anything but conventional, though. They were turtles, drumming monkeys, and twitching eels. My partner and I had the most bizarre conversations, saying “Hey, we could pull on the cow’s udder.” – “Cool, that makes a beeping sound. Do it again!” The resulting song was understandably mediocre, and we thankfully declined the staff members’ offer to download it for us.

The authors Damian Kulash Jr. from the band “OK Go” and VR pioneer Chris Milk created the experience in collaboration with Oculus, meaning chances are good that we might soon all be able to play in loopy bands.

Change of Perspective

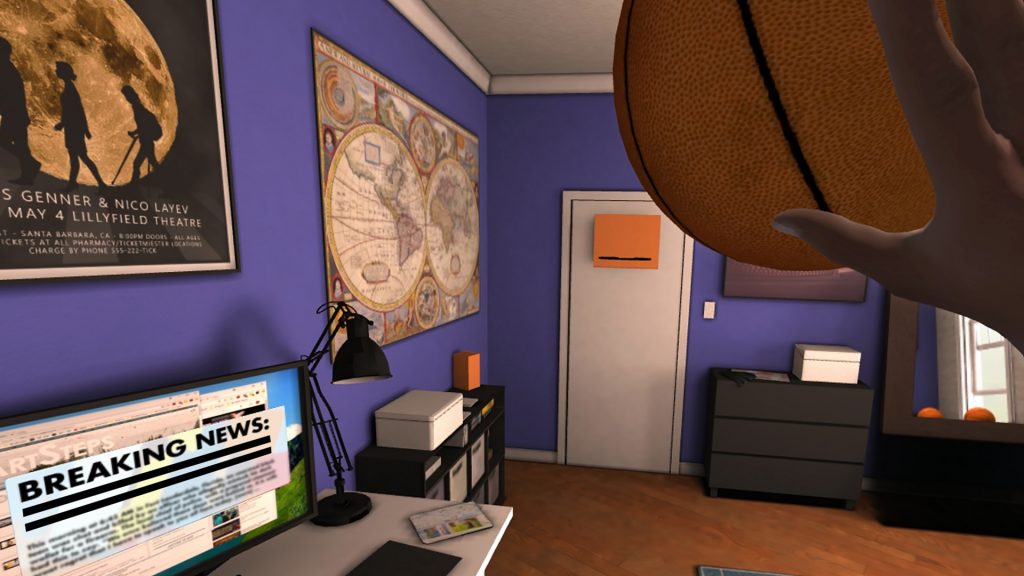

To close things off, another serious topic. What, if not VR, is best-suited for a change of perspective? – Which is exactly what 1000 Cut Journey draws on. As a spectator, I became Michael Sterling, a black man, and lived through his life in fast-forward. I played with other kids who made fun of my skin color and was brutally assaulted by a police officer as a teenager, while they paid no attention to my white friend. As an adult, my Ivy League degree appeared to be of less importance than my skin color during a job interview. The entire experience is computer-generated, only the other people are real (though unfortunately very two-dimensional). Its interactivity catalyzes the player’s transformation into the avatar they see themselves as in the mirror.

VR and avatars tend to be a tricky endeavor, especially when the avatar captures the entire body – things can get weird. Hands bending in ungodly directions, legs flapping around like those of a teenager who has grown too much, too fast. That is why games rarely display an avatar as an entire person, but rather as two hands and a head. This usually suffices to make you and others feel present in a scene. Justifiably enough, this would not have been enough for 1000 Cut Journey, yet I must say that I would have rather foregone interactivity if I could have been able to see a real person in the mirror. Having said that, the experience demonstrates how VR can be employed in the fight against racism – or prejudice in general.

To those interested in a more detailed examination of this topic, I highly recommend reading this article by Engaget.

Translated by Jan Mc Greal

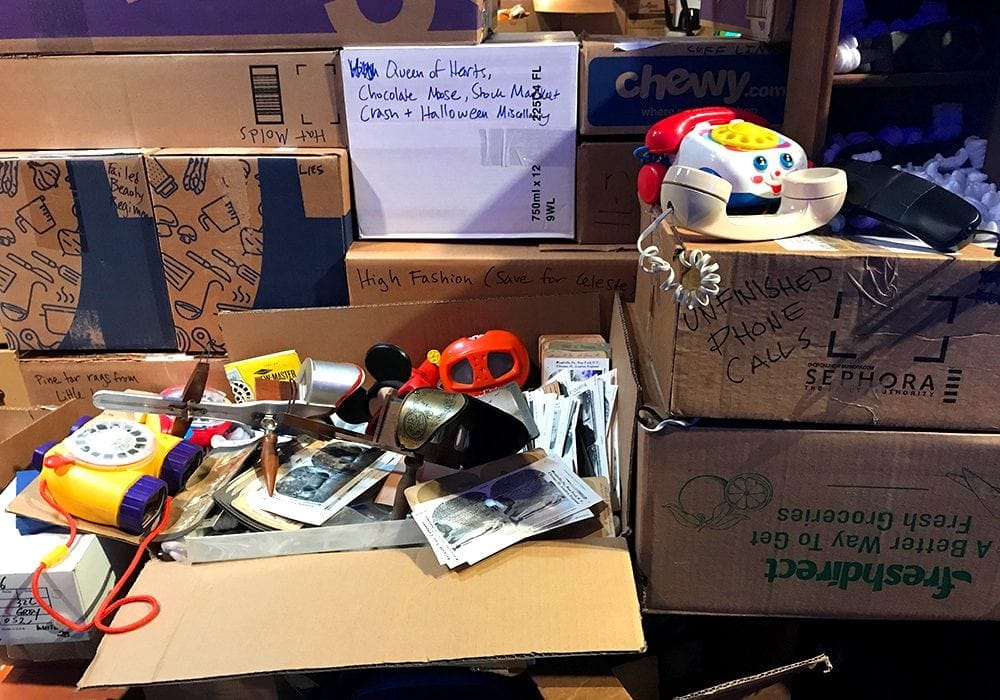

![Objects in Mirror are closer_Tribeca 2018 © Pola Weiß Yet more boxes. Apropos, "Objects in Mirror […]" was inspired by an immersive theater installation.](https://vrgeschichten.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Objects-in-the-Mirror-2-1000x700.jpg)