About two years ago, I caught a glimpse of the beginning of the VR film BattleScar – instantly, I fell in love: with the film, its main protagonist, Lupe, the rhythm, the music, the style, the groove. Now, it has finally reached completion and awaits its release. One thing is certain: it’ll be the party of the year!

A Stroll Through New York

My husband and I were walking through New York City’s Lower East Side on a Spring morning of 2018, blessed with the chance to spend three months in this sprawling, marvelous city.

Then, I spied something: I (more or less gently) poked my companion’s side and pointed at a house by the side of the road. “That looks just like in BattleScar!” I bellowed before making a beeline for the house, camera in hand. My poor husband stood there, dumbfounded, unknowing of the meaning of the word “BattleScar” or the house itself. They meant something to me, however – and what a treasure I had discovered.

BattleScar is a roundabout 30-minutes-long non-interactive animated film in virtual reality, the first chapter of which debuted 2018 at the Tribeca Film Festival. Unlike me, my better half hadn’t attended the festival, so there was no way for him to know what had delighted me so.

Back then, the VR film had knocked me off my feet – almost literally. Never had I experienced such pace, such rhythm in virtual reality. This may be owed not least to the topic at hand, which is music. Or, put precisely: seventies’ punk in New York.

BattleScar – Punk Girls Conquer the World

Back in the day, the clubs of Bowery hosted them all: Patti Smith, The Ramones, Talking Heads, Blondie, The Runaways. I certainly can’t call myself a punk connoisseur – however, while writing this, I simply couldn’t resist the urge and started listening to this Spotify playlist all day long:

You should, too! You will definitely read faster listening to it. Yet, it is also worthwhile for another reason as the playlist only features punk bands headed by women. Women played an important role in the emerging punk scene and, gig by gig, took their rightful place in music history. BattleScar revolves around exactly this, as should be clear through the subtitle: “Punk was invented by girls.”

The film is set in 1978. After having run away from home, the 16-year-old Lupe, an American girl with Puerto Rican roots, finds herself in a juvenile detention center. There, she meets Debbie, pretty cool and also pretty wild. Barely outside, Debbie takes Lupe to New York City’s Lower East Side and Alphabet City – straight into the emerging punk scene. Together, they encounter their idol, the singer Elda, discover exciting new places and start their own band – even though neither of them can play an instrument.

For the two directors, Martin Allais and Nico Casavecchia, the film project gave them the perfect opportunity to finally take a closer look at punk rock. They had been interested in this topic for a while, as the two of them tell me during an interview during the film festival in Venice in Summer 2019, where BattleScar premiered in full length and featuring all three parts.

Martin: Both of us started digging [into punk music]. We tried to understand the late 70s punk versus UK punk versus US punk versus West Coast punk versus East Cost punk, girls’ punk, men’s punk – everything. Now we know. It was a good excuse to get into those archives.

Ode to a Past Age

Mercedes Arturo, Nico’s wife, gave the impulse for the project. While the couple lived in New York City, she read the book Just Kids by Patti Smith. She and Nico perceived the world it described as truly immersive – and wholly different to the New York that they experienced on a daily basis.

The final idea was incepted with Martin, Nico’s longtime friend. “Why not travel back in time to the New York of the late seventies?” they wondered. Back to a time they both loved and revered. Virtual reality appeared as the perfect medium – and so, their first collaboration was born.

Hence, it’s no coincidence that BattleScar really features three protagonists. Besides Lupe and Debbie, it’s the city itself: New York. This shines through in numerous allusions: street names, quarters and sounds meld together to form a highly atmospheric collage. Viewers follow the two young women through the city in a trance-like state electrified with anticipation.

This way, BattleScar captures what they had internalized from their reading, Nico and Martin recount. Whenever you were walking through the streets of Bowery, you’d run into an acquaintance. “You know who’s playing tonight? Come to the concert!” they would call. Music around every corner.

BattleScar is a Treasure-Trove for Immersive Storytelling

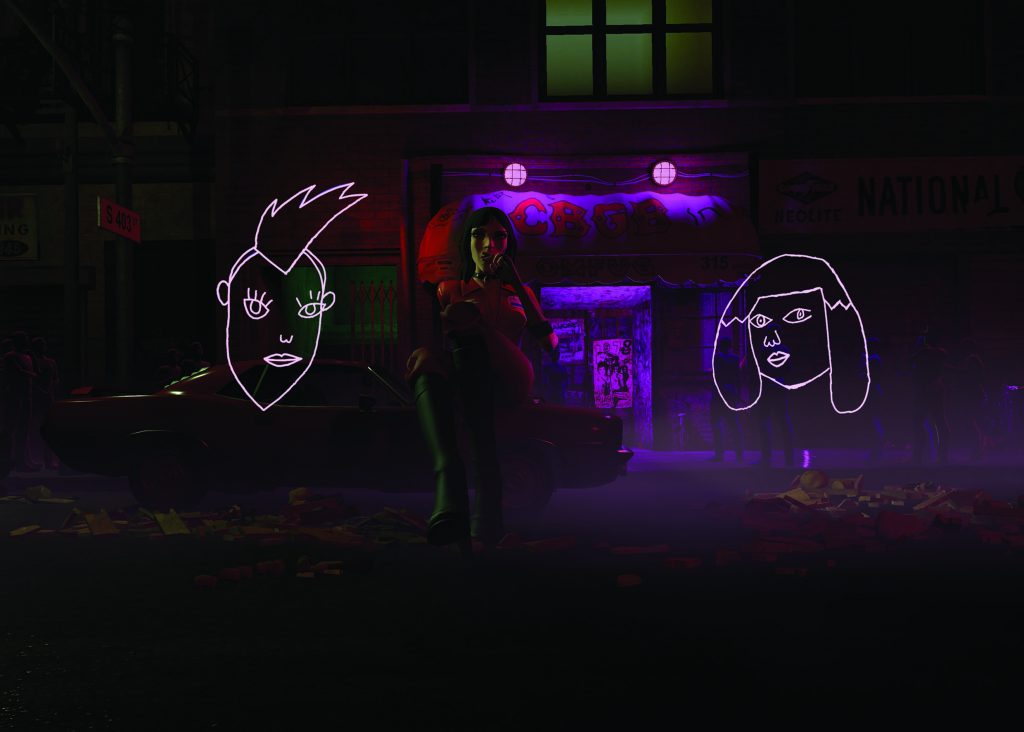

To resurrect that seventies feeling, the two directors created an entirely novel visual language: at times, the films zooms out of the picture to overlook the city from a bird’s eye perspective. In a sort of 3D city map – which, incidentally, is based on a real city plan – Lupe and her friends scurry from one point to the next.

What might feel unfamiliar at first turns out to be a fabulous idea: with this technique, Nico and Martin essentially found the VR equivalent to film’s master shots almost in passing. “Master shot” refers to the shot at the start of a scene intended to help spectators understand the setting through geographical and contextual information. This kind of localization in virtual reality? It’s possible now.

Elsewhere, too, the directors venture some rather wild experiments in BattleScar. They wanted to avoid making something boring, they tell me. To my astonishment, they hardly let other virtual reality productions influence their work.

Martin: We don’t see a lot of VR, to be honest. We had seen some experiences here and there, but we’re not crazy about that in general, because we’re more into making them. And we ask ourselves: how do we make this interesting and exciting for people and for us? I think, everything responds to what we like. We just tried to find a language instead of defining a language. So BattleScar is trying to find something.

To find a language – they certainly did. By trying different things and via many discussions, a beautiful synergy arose that can perhaps only by attained between friends. BattleScar immediately impressed me with three of the friends’ ideas: word overlays, playing with scale, and the voiceover itself.

Transitions and the Written Word

Thinking back on BattleScar, my mind immediately wanders to words: capitalized letters, written in a scrawly script and launched into the room. When Lupe speaks – she narrates the film as a voiceover – select words appear in written form, overlaying the scene. Not only did it make the English language more accessible to me: this is actually a new approach for VR. How did they get to this point?

Nico: There’s Lupe’s journal that is very important in the first chapter, because it is a recollection of her memories. For this, we already had started developing the style of the journal, had started drawing letters. And at some point, we– probably by accident – figured that this world together with the voiceover was overwhelming. People’s cognitive capacities are limited and VR is a new medium. And we happened to find that we can use the words as an anchor. They bring you back to the story, and help you to pay attention to the voiceover.

This might not be a novelty in the world of graphic design, interjects Martin, who also works as an illustrator. However, it is in virtual reality. Content-wise, it’s a perfect fit for BattleScar: graffiti, too, belongs to punk – and graffiti implies rebelliousness. And rebel it does! The film proceeds faster than anything else I have seen in VR to date.

The driving factor might be found in the well-executed transitions: time and again, scenes are augmented with environments that roll in from the background (not unlike in the theater), while in other scenes, Nico and Martin play with spotlights and set lighting. Then, once again, the words return to the screen to facilitate a perfect transition from one scene to the next simply by grabbing the viewers’ attention for a second.

Big Now, Small Later – BattleScar Experiments With Scale

Another contributor to the captivating rhythm is the inventive manipulation of scale: in one moment, you are huge, peering down at the world; in the next, you’re catapulted back into Lupe’s and Debbie’s surroundings and can look at them face-to-face. Most of the time, the film is told in the third person. However, every now and then, the story takes on Lupe’s perspective.

There’s a scene – the two teenagers run into an angry petty criminal – where Lupe (and with her, the VR audience) suddenly shrinks in size. The gun pointed at their faces keeps growing, becoming more threatening every second. Such moments resulted quite intuitively, Nico and Martin tell me. They would try different ideas, discuss them a lot and then continue experimenting. The question in the back of their heads would always remain: which character is stronger at this moment? Who is powerful, and who feels small and vulnerable?

Accordingly, BattleScar further cultivates the “dollhouse” style, a style featured in many VR productions now, for example in the film Allumette or the game Moss. Instead of steadily overseeing the world as a quasi-god, BattleScar places deliberate emphasis and creates distinct experiences, allowing viewers to get very close to the protagonists.

Voiceover: Rosario Dawson’s Sublime One-Woman Show

While Martin primarily took on responsibility for music and atmosphere, Nico tackled the film’s plot. However, an actual script with dialogs and directions never existed. Instead, he wrote the characters’ dialogs much like a story, a novel – a kind of precursor to what would have been a script.

The directors took this novel and presented it to Rosario Dawson for their first meeting. Rosario promptly began to read aloud, speaking for all characters. This spontaneous idea turned into a stylistic cue: Lupe narrates the entire story as a voiceover recollection of her memories. This feels comedic and strange at once when a bearded giant shouts his threats from across an intersection in Lupe’s voice. It undeniably strengthens the viewers’ ties with Lupe, who you fell closer to with every encounter.

Rosario Dawson, herself of Puerto-Rican descent, carries us through the story with a fantastical lightness: she naturally incorporates “Spanglish” words and generally alternates between Spanish and English with charming effortlessness. You see – and hear – that Lupe’s life takes place in between two cultures.

Rhythm and Pace – It’s the Mixture That Counts

Writing BattleScar was a challenge, Nico admits. On the one hand, there’s the story with its multitude of dialogs, on the other hand, numerous immersive impressions cause a sensory overload. He had to strip the script down to its bare bones to help viewers follow the story emotionally. As such, while the first chapter tears ahead at an unrelenting pace, the next two chapters take on a calmer, almost contemplative stride. There, the story needs more „meat,“ Nico explains.

Nico: Chapter one sets up the world and the characters, but if you want to have an emotional payoff you need to slow down and be with the characters, develop their relationship and spend time with them. That is why we always look for contrast, if you have a high-paced scene you need to balance that with a more intimate one, otherwise you risk numbing people.

Not to worry, as this does not happen even for a single moment. The story of Lupe and Debbie is an ode to animated film and a tribute to virtual reality. Whichever filmmakers are seeking inspiration for transitions and scaling, they need not look further than BattleScar. I can hardly wait for what the Allais-Casavecchia duo has in store for us next.

Release in 2020

BattleScar is a coproduction of ATLAS V, 1stAvenue Machine, FAUNS and Arte and is supported by the platform Kaleidoscope and is funded by the French government. The film’s exact release date has not been set yet; however, it will likely not be long: the Arte homepage cites “beginning of 2020,” where the film will also appear in German and French language versions.

Translated by Jan Mc Greal