One long year, I waited, and I hoped: when will I be able to see it? And where? For Wolves in the Walls promised nothing short of greatness. I finally got the chance to try the VR experience for myself at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival. Not only that: after the fact, I sat down with the producer, Jessica Shamash, and the director, Pete Billington, who let me in on some of their secrets. This article is the first in a series revolving around the project that holds such importance for storytellers.

“We set out to tell a great story—we ended up building an encyclopedia of everything we know about interactive storytelling” Pete Billington

Lucy and I

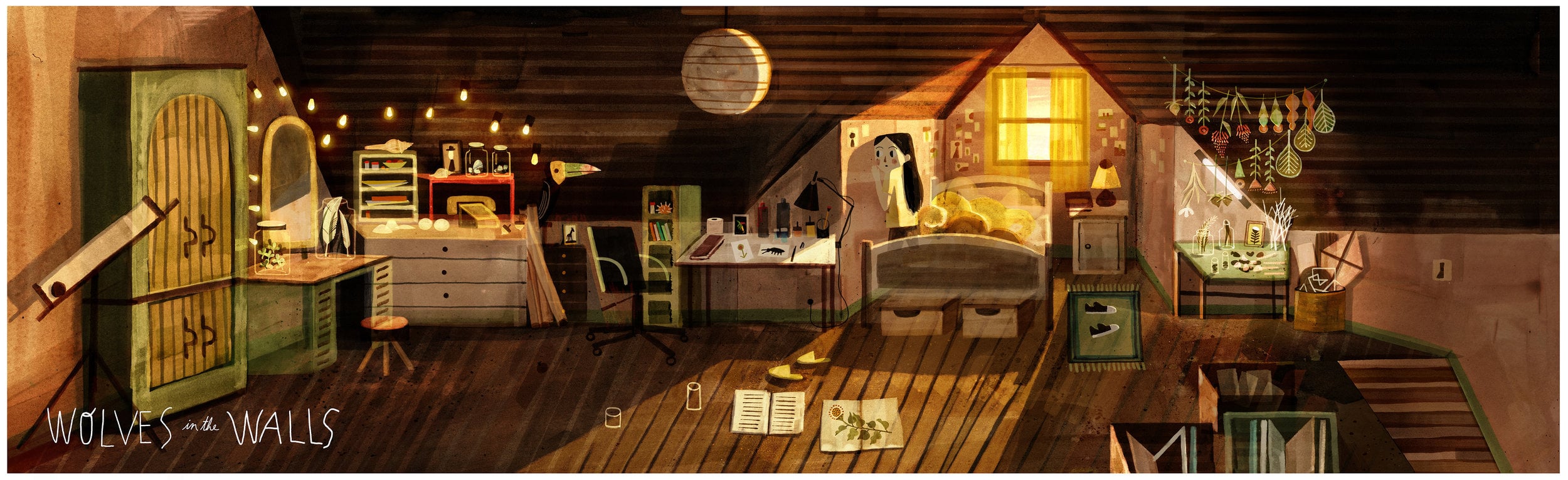

Standing in a small room, VR goggles hugging my head, I can still hear the muffled noises spilling over from the bustling festival as I move away into a different world. Then, I’m greeted by a girl in a red-and-white striped sweater, frowning at me from below and contemplating aloud, “Oh, I drew you kind of tall.” She does a bit of wiping, draws a few lines and makes a fanning motion—and, what do you know, I have shrunken. We face each other at eye level now, Lucy and I, and we get acquainted. I am her new friend; someone she can confide in.

For Lucy has a terrifying suspicion she must investigate. Neither her mother nor her father believe her, so she turns to the only practical solution: drawing herself a companion—me, the Watson to her Holmes. Together, we will try to discover the source of the sinister sounds that have been emanating from the walls in the house since a long time. Are they really wolves?

Eight-year-old Lucy is the protagonist of the VR animation film Wolves in the Walls, which is based on the eponymous novel written by Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean. According to the director, Pete Billington, the plot is especially well suited to a character-driven story in virtual reality, as it explores children’s fantasies and emotions. The goal is to make the audience feel like a child again.

The team has worked on the project for some years now, and there is still more to be done. I had the chance to experience the first two chapters. Jessica and Pete hope to premiere the third and last chapter before the end of the year. The project started at the Oculus Story Studio, but Facebook closed that in 2017, and so, Lucy and her fellow adventurers were lucky to find a new home: together with a part of the team, they moved to San Francisco-based Fable Studio.

Realistic Characters and virtual beeings

Critics and VR enthusiasts were full of praise following the first chapter’s premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in 2018. One of the main reasons for this reaction was a certain technical innovation employed by Wolves in the Walls: Lucy, my friend and arbiter (she can be quite authoritarian) is not a run-of-the-mill animation.

Her creators call her a “virtual being.” For in the background, Wolves in the Walls boasts technology that adapts the VR experience to my behavior in real-time. Am I taking a picture of the wrong subject? Lucy scolds me. Am I too slow? She tells me to hurry up. Luckily, she is thrilled when I do the right thing, too.

This technique develops its greatest effect in the details; such as when Lucy approaches me, takes my hand or dodges out of my way—her movements continually adapt to mine. Moreover, it feels like she is truly looking directly at me, no matter where I’m standing. The producer, Jessica Shamash, explains to me the amount of knowhow needed even for such seemingly small interactive moments:

“It’s eye contact in a natural intuitive way; just the way that you and I are making eye contact right now. And it’s really important to find the line: when do you look at someone’s face, when does she look at your mouth, when are you looking at her mouth? There are all these subtle things that are involved, rules that you have to abide by to really have a realistic character that feels emotionally connected.”

Indeed, I feel respected and liked by Lucy when she looks at me. This form of interaction is one of many tricks that the team behind Wolves in the Walls lifted from the theater. What that looks like in detail and which mechanisms are pertinent to storytelling, I explain to you in the second article for Wolves in the Walls.

Discover what else Fable Studio has planned for their interactive characters in this video:

Wolves in the Walls Creates a New Form of Interaction in VR

In Wolves in the Walls, interactivity arises primarily through objects. Lucy hands me a magnifying glass, and I take it. The transitions are so fluid that I don’t even notice them most of the time. The story doesn’t pause for a moment, as tends to be the case in many interactive VR experiences: until the user finally pulls the lever, opens the right page in the book, or walks into the next room. In this great text on No Proscenium, Pete writes, “Now we had a new construct: an experience where audience agency would not hold narrative hostage.” He went into more detail on this in the course of our conversation:

“You’re making many choices without thinking about them. That was the hardest thing for us to do well. We always want to make your choices intuitive, subconscious and also invisible. So if you picked up the camera and you took a photo: What would happen if you didn’t? She would have figured out a way to keep going with her story.”

He mentions a scene that happens at the end of the first chapter, in which I’m supposed to collect proof that the wolves are real and they’re sitting in our walls. To do this, Lucy hands me an old Polaroid camera, which I promptly misuse to take a picture of Lucy sitting and reading something to me. Immediately, she looks up from her book and puts me in my place, “Not me, dummy, the wolves!” And so, I decide to take things seriously and take more pictures. And I do find something…

Jessica alludes to this scene’s dramaturgical significance:

“It’s one of the most significant things. It’s the picture that you take as what sets her off on her journey. Your pictures is what has given her this proof that she’s been looking for. That’s the inciting incident.”

Dramaturgy: Twigs, Not Branches

Handling the camera remains as one of the most important tasks, even if I run into more opportunities where I can help through the course of the story.

In fact, according to Pete and Jessica, the VR experience features more than a hundred little decisive moments. However, branching storylines or even multiple endings were never part of the concept. Pete explains this as follows:

“Instead of branches we call them twigs—like the little tiny branches that always come back to the main trunk of the tree. Because she does have a character arc. She does have a goal.”

And so, I find myself on a breathless chase through the house. Together, we eavesdrop on the walls and mark the spots where we think we heard something—much like real detectives. All along, Lucy calls the shots. While my actions certainly carry significance, they only have a limited effect on the story. Pete explains how this came to be:

“When you play a game, you’re the main character and the story comes around you. We wanted the story to be Lucy’s story but you’re important to her. You’re her friend. And so just like when we’re helping a friend, we can have an impact on their lives in a positive or maybe negative way. But they’re still going to make their own choices.”

The Users as Sidekicks

To this extent, Wolves in the Walls capitalizes on a trick that I have heard mentioned from a number of creatives in the realm of VR: you don’t have to choose between the first person perspective common to videogames and third person narration, as is usual for film.

While the former affords the player a lot of freedom, their roles and objectives tend to remain superficial. It is the classic gamer I. This works well for action-driven games, but falls short in the application of drama. On the other hand, if users view the VR experience as a ghost from the third person, the story may enjoy more depth—yet it can also become very frustrating to be damned to idleness in a medium so fabled for its interactivity.

Fortunately, a balance can be struck: many videogames nurture a creature, a companion, that follows the protagonist (who is traditionally, at once, the player in videogames), gets things done, yet hasn’t much to say themselves. It can be a dog, a little dragon, a son or a daughter. Or an imaginary friend.

For VR experiences, letting the user jump into the role of the companion instead of the protagonist kills two birds with one stone: they play an important role, are involved in the action and no longer banished to the sidelines as spectators. And at the same time, they get to watch the protagonist fight their own battles. The heroes can then develop their character to greater depths, which is absolutely crucial for suspense and empathy.

In Wolves in the Walls, the result is a linear story interspersed with non-linear moments. Not a film, not a game, but something in-between.

Curious for more? Read more on the subject here

Read the second part of my series on Wolves in the Walls here: What can VR storytellers learn from immersive theater?.

The last installment of my series of articles on Wolves in the Walls will appear here in due time. It will explain why VR storytellers have the potential to be the purest superheroes.

Get to know the theory a bit more here: What Distinguishes an Interactive VR Film from a VR Game?

And here are a couple of examples in 360 degrees from last year: interactive films in 360 degrees.

UPDATE August 2019: The first two chapters Wolves In The Walls: It’s All Over are now available at the Oculus Store for Oculus Rift and Rift S (early access).

UPDATE November 2019: Wohooo – the third an final chapter is NOW available for the Oculus Rift. Go for it!

Translated by Jan Mc Greal